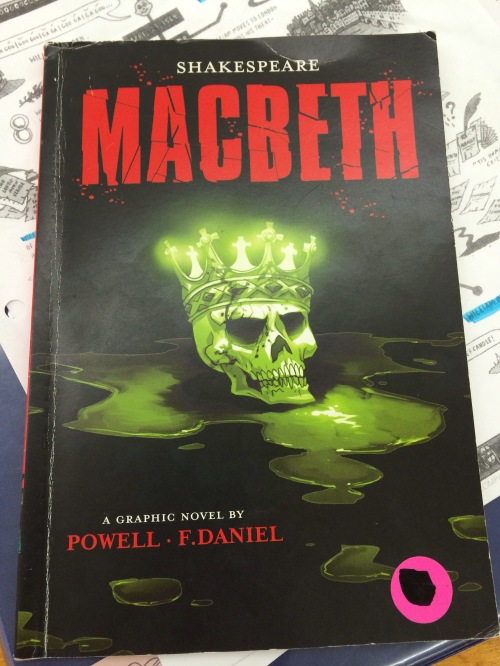

I stumbled upon this video today and wondered how reading William Shakespeare’s Hamlet might connect to a very real calamity in Cape Town, South Africa, where, after a three-year drought, water levels are almost at zero.

Day Zero: how Cape Town stopped the taps running dry

I had a chance to work with some wonderful teachers a few days and I wondered out loud whether students need the teacher to play the role of the ‘bridger’:  that is to say, the teacher needs to show students how any lesson bridges or connects to ‘real life’ — or anything for that matter.

that is to say, the teacher needs to show students how any lesson bridges or connects to ‘real life’ — or anything for that matter.

So, with that in mind, I wondered how might we connect Hamlet to the water emergency in Cape Town?

(The reason, for this exercise, I have chosen Hamlet is that it is used widely, usually in senior grade levels, and I wanted to explore how a ‘core’ text such as Hamlet might be used to connect to other issues and topics.)

- Problem-solving:

- What makes for effective problem solving? What are the criteria to effective problem solving?

- What do effective problem solvers do when faced with a very difficult problem?

-

- How does a person have to think, behave, interact with others, speak in order to effectively solve a problem?

- Is Hamlet an effective problem addresser / solver? Why or why not?

- How did the people and the government of Cape Town, South Africa handle their problem? According to our criteria, did they effectively address their problem?

- Compare the crisis of Cape Town to Hamlet.

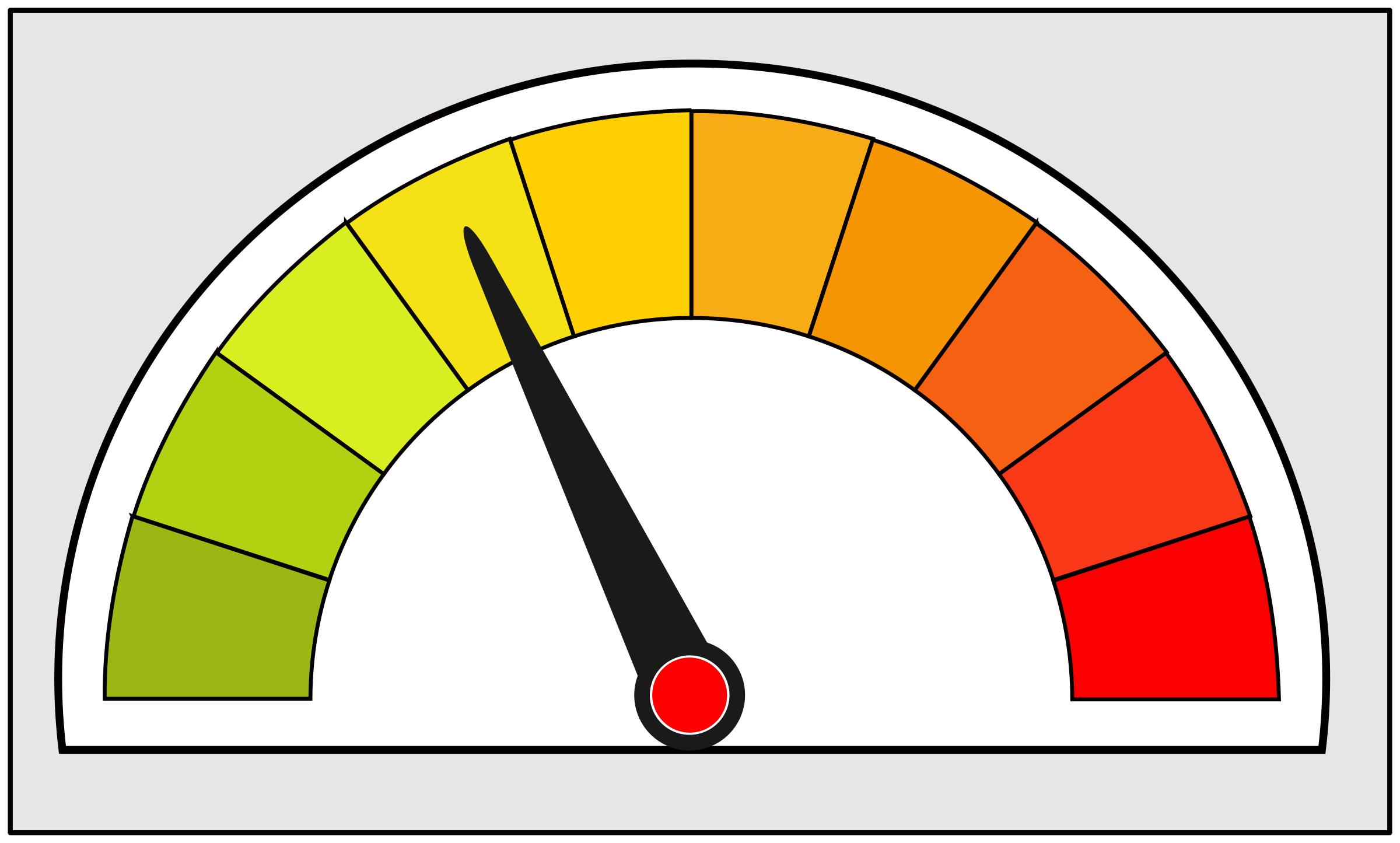

- Is it possible to place both of these crises on the same scale o

f urgency? That is to say, is Hamlet’s personal problem as urgent or critical as Cape Town’s water problem? If we use a form of meter to ‘measure’ the intensity of a crisis, where would Hamlet’s problem fall on that meter according to a) him? b) his friends and family? c) his country? Why do you say that?

f urgency? That is to say, is Hamlet’s personal problem as urgent or critical as Cape Town’s water problem? If we use a form of meter to ‘measure’ the intensity of a crisis, where would Hamlet’s problem fall on that meter according to a) him? b) his friends and family? c) his country? Why do you say that?

Extension:

- What if I started off my entire unit with that essential question: What makes for effective problem solving? Or the other question: What do effective problem solvers do when faced with a major, seemingly unsolvable crisis-level problem? And then what if we used Hamlet as case-study or a base-line or a comparison in amongst other texts, such as Apollo 13 or The Martian or the Cape Town water crisis?

- And then what if we tap into the work of Garfield Gini-Newman and The Critical Thinking Consortium who promote ‘criterial thinking’, which is making a sound decision based on criteria and evidence?

- And once we have that thinking framework, what if students were invited to engage in free reading and they were to look for other ‘case studies’ of how people solve problems?

- And what if I asked these students to write about how they have solved problems in their own lives?

- Last question: Is Hamlet the best ‘vehicle’ for exploring this topic?

UPDATE:

- The Cape Town water crisis video explores the impact the Day Zero water initiative had on citizens in the city, particularly those below or at the poverty line, who tend to be people of colour. An area to explore could be the potential

impact a solution might have upon another person, a group, society in general. For example, how do Hamlet’s choices impact others? Is this solution still effective then?

impact a solution might have upon another person, a group, society in general. For example, how do Hamlet’s choices impact others? Is this solution still effective then? - What wisdom might we take — both positive and negative — from Hamlet’s story and the Cape Town initiative that we could use as lessons for our own lives both now and in the future?

ng only what have been deemed ‘the best or important novels’ will have on them? Kelly Gallagher, in his book

ng only what have been deemed ‘the best or important novels’ will have on them? Kelly Gallagher, in his book

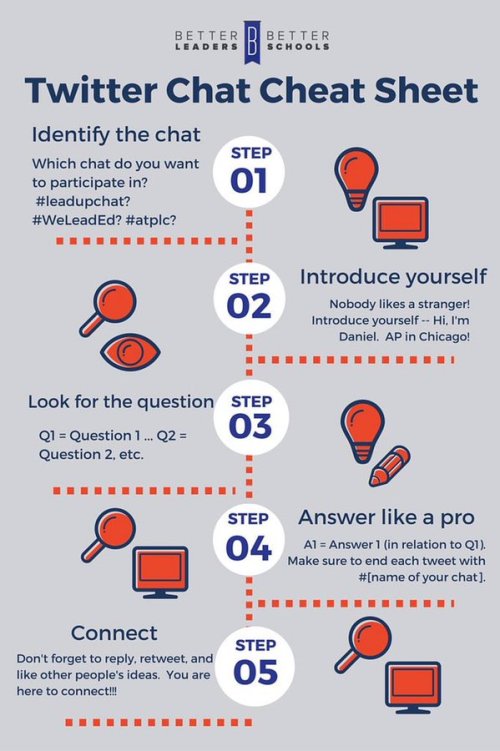

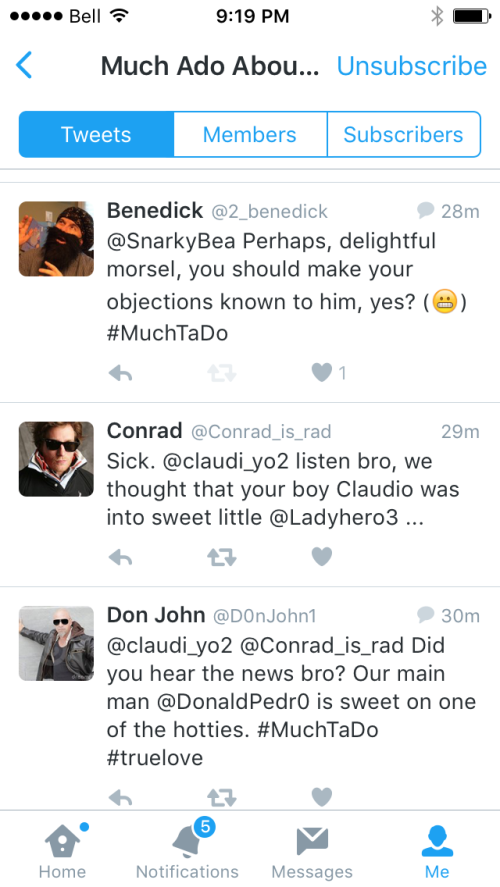

Last night, I participated in a Twitter (or tweet chat) hosted by educators in Ohio under the hashtag #OCIRA.

Last night, I participated in a Twitter (or tweet chat) hosted by educators in Ohio under the hashtag #OCIRA.

And what a thrilling (yes, thrilling) experience to have other educators from another part of the world acknowledge and even affirm my ideas and experiences. Indeed, how thrilling it was to have Tanny McGregor herself like and retweet some of my posts. Amazing.

And what a thrilling (yes, thrilling) experience to have other educators from another part of the world acknowledge and even affirm my ideas and experiences. Indeed, how thrilling it was to have Tanny McGregor herself like and retweet some of my posts. Amazing.